The Wright Brothers vs Samuel P Langley

What does it take to succeed at solving a really hard problem?

"If birds can glide for long periods of time, then… why can't I?"

Wright Brothers

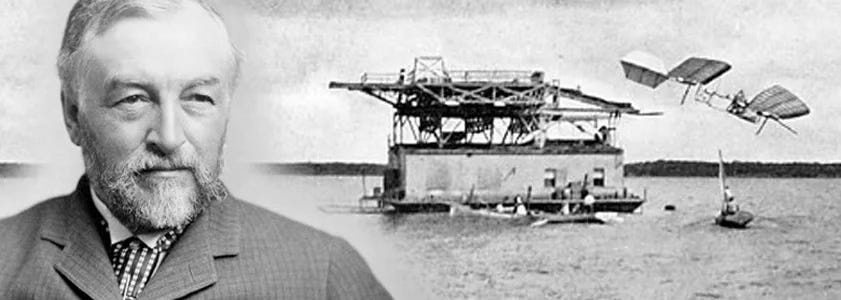

Samuel Langley and the Wright brothers represent two pivotal chapters in the history of aviation.

In the early 20th century, the world knew that powered flight was within reach, and two distinct stories emerged from this ambition. On one side was Samuel Langley, a respected scientist with the backing of government funding and prestigious accolades. On the other, the Wright Brothers, Orville and Wilbur, humble bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio, driven by curiosity and unwavering resolve.

Their contrasting journeys toward the same dream offer invaluable lessons on leadership, innovation, and the essence of perseverance.

Samuel Langley was an astronomer, a physicist and a pioneer in aerodynamics, deeply interested in understanding the principles of flight. Langley was a man of reputation, revered in academic circles. As the third secretary of the Smithsonian Institution he was supported by government to fund his experiments, focused on large, powered flying machines, such as the "Aerodrome," which was modeled after birds, which he built and tested between 1894 and 1903. Langley's approach was deeply theoretical, relying on his understanding of physics and aerodynamics. His work included the development of early powered aircraft models, which actually flew in the early 1900s, but struggled with reliability and control. His Aerodrome was not successful in sustained flight.

Samuel Langley is recognized primarily in the context of aerodynamics and early flight experiments, and he is often viewed as a brilliant but ultimately unsuccessful innovator in powered flight.

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur Wright, were bicycle manufacturers who became fascinated with flight through their own curiosity and experimentation. Their motivation was more practical and their focus was on creating a controllable and sustainable flying machine. The Wrights took a hands-on approach, conducting extensive field tests and emphasizing control and stability in their designs. They developed the three-axis control system, which allowed pilots to steer the aircraft effectively. They made significant advancements in aircraft design, including the invention of the wing warping technique for lateral control and the use of a lightweight engine, which led to their breakthrough with the first powered flight on December 17, 1903.

The Wright Brothers are celebrated, plain and simple, as the inventors of the first successful powered aircraft and their legacy is firmly established in the annals of aviation history.

The Humble Grit of the Wright Brothers

The Wright Brothers emerged from a world far removed from the halls of academia. Orville and Wilbur shared a passion for flight that transcended their very modest beginnings. They had no government grants, no extensive laboratories, and certainly no elite status to lean on. What they did possess was an unyielding desire to conquer the skies, fueled by their hands-on experience as bicycle mechanics.

The Wrights had a true spirit of innovation which led them to approach the goal through relentless experimentation. For instance, they built their own wind tunnel, engaging in a rigorous process of trial and error. Every crash, every setback became a lesson learned. They did not shy away from failure and they showed great resourcefulness.

Through perseverance, innovative thinking, the collaboration with experts and hard work, the Wright Brothers achieved what many considered impossible and on December 17, 1903, in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville Wright piloted the first successful powered flight, soaring for 12 seconds that would change history.

Your endurance in the face of challenge defines your leadership legacy.

Leadership Lessons

The contrasting outcomes of these two stories serve as teachers of leadership.

1. Vision Must Be Grounded in Action

A compelling vision is not enough, it must be supported by sense of urgency to prioritize, bias to action to execute, and a willingness to pivot to adapt. Samuel Langley’s vision was undeniable: he wanted to be the first to achieve powered flight, but when his aircraft failed, he didn’t lack vision, resources or the will to go on, he lacked the framework to iterate, learn, and evolve.

In contrast, the Wright Brothers combined their vision with relentless execution. They built gliders, tested control systems, collected data, refined their designs, and adjusted based on results. Their progress was not about big, singular bets but about consistent, incremental learning.

A visionary leader does not wait for the “perfect” strategy before moving forward.

Instead of debating endlessly, translate vision into prototyping, testing, and refining. Embrace a feedback-driven approach, ensuring that decisions are continuously informed by real-world insights rather than assumptions. Execution, not prestige, wins the game.

2. Innovation Demands Risk-Taking

Innovation requires embracing failure as part of the journey through resilience. Langley, despite his ambition, played it too safe. He adhered to conventional thinking, relied on government funding to eliminate risk, and lacked the courage to pivot when his model failed.

The Wright Brothers, in contrast, embraced risk as fuel for progress. They saw failure as data, their approach was one of continuous learning through controlled failure, leading to small but critical insights that compounded over time. They were willing to endure setbacks as the price of genuine breakthroughs.

Leaders who fear failure more than stagnation will always be outpaced.

Establish an innovation culture where risk-taking is strategic, iterative, and encouraged. Reward teams for pushing boundaries rather than just optimizing existing processes. Encourage bold thinking, but tie it to disciplined execution.

3. Perseverance is the Price of Leadership

Leadership for innovation is a long game. The Wright Brothers had every reason to quit, from financial struggles and failed experiments to public skepticism. But they kept going because they were committed to solving a big problem. Their perseverance was what ultimately allowed them to succeed where others had given up.

Every leader will encounter resistance, setbacks, and unforeseen obstacles. What separates the great from the forgotten is the ability to persist through discomfort.

When initiatives stall or markets shift, adapt, refine, and keep moving forward.

Setbacks should fuel greater determination, not signal defeat.

The Wright Brothers’ Lesson for Modern Leaders

Langley had every advantage: resources, influence, and recognition. The Wright Brothers had none of these, but in the end, they solved the hard problem while Langley, a true expert, had to watch it from the sidelines.

Always ask yourself these questions when faced with challenges:

Are you building prestige or solving problems?

Are you waiting for certainty or moving forward with agility?

Are you leading with resilience or retreating at the first sign of failure?

Are you signaling defeat when handed a setback or are you doubling down efforts?

Are you still committed to the mission, or are you just chasing external validation?

“My brother and I became seriously interested in the problem of human flight in 1899 ... We knew that men had by common consent adopted human flight as the standard of impossibility. When a man said, “It can’t be done; a man might as well try to fly,” he was understood as expressing the final limit of impossibility.”

Wright Brothers

BONUS TRACK

I don’t do well with oversimplifications!

Simon Sinek is undeniably a great communicator, and many of us have learned valuable insights from his work. However, there is one story in his renowned Start with Why that is not just flawed but dangerously misleading. It’s about the way he presents the comparison between Samuel Langley and the Wright Brothers, a narrative that suggests that a compelling vision is the ultimate driver of success, while personal ambition only is a lesser and detrimental force; and he goes into saying that this was the difference between the Wright Brothers (vision) and Langley (greed).

Not only this is not accurate to reflect who these men were, but such oversimplification distorts the true dynamics of achievement and innovation.

If you want to be a free and critical thinker, you must always challenge these type of narratives to ensure you can operate with clarity and precision.

Langley did not lack vision or passion or commitment, The Wright Brothers were not just propelled by a vision bigger than their own pursuit for glory. They had different working assumptions, different operating frameworks and different contexts in which to present their progress, different accountability models and different backgrounds. All that put together is required to do justice to a proper analysis of each journey.

Take 3 minutes to listen Sinek tell the story in a way that fits his framework to explain success

Why Simon Sinek’s Narrative Misses the Mark?

Simon Sinek often cites the Wright Brothers as a case study in the power of “starting with why.” explaining that Langley’s “Why” was prestige while the Wright’s was passion for flying, which in turn explained why Langley abandoned his work when he realized he was not going to be the first, as others had already succeeded.

Not only is a simplification but it is not true to history. The success of the Wright Brothers wasn’t driven by a grand vision and a selfless ‘Why,’ but by a relentless commitment to solving a specific engineering problem, how to control flight mid-air.

Far from lone visionaries, the Wrights were pragmatic problem-solvers who built on the work of others, including the one of Samuel Langley, a well-funded pioneer whose research provided critical insights. Langley’s failure wasn’t due to a lack of a selfless vision because he was only after prestige, as Sinek claims; but due to external factors, a wrong or limited way to look at the problem to solve, technical limitations, and timing. The Wrights had a different approach at solving the problem, and were able to be successful by iterating relentlessly, experimenting with gliders, and very important, by bringing in an engine specialist with the technical expertise they needed.

Sinek’s oversimplified framework suggests that success hinges primarily on an inspiring “Why,” which will drive you no matter what. Of course purpose matters, often execution, expertise, and timing matter as much or more.

Selfless visions alone don’t build airplanes, engineering does.

"If we worked on the assumption that what is accepted as true really is true, then there would be little hope for advance."

Wright Brothers

P.S. Before I go, here you have “The Treat,” where I share some of the music that made me company while writing … Enjoy as you bid farewell to this post

“Lead yourself, Learn to live. Lead others, Learn to Build.”

If you enjoyed reading this post consider subscribing to the newsletter for free, joining the community and sharing your thoughts.

Enjoyed the read!