The Perception of Reality is not Reality.

The Interpretation of Reality is not Reality.

The Representation of Reality is not Reality.

Welcome to another edition of “Students of Leadership,”

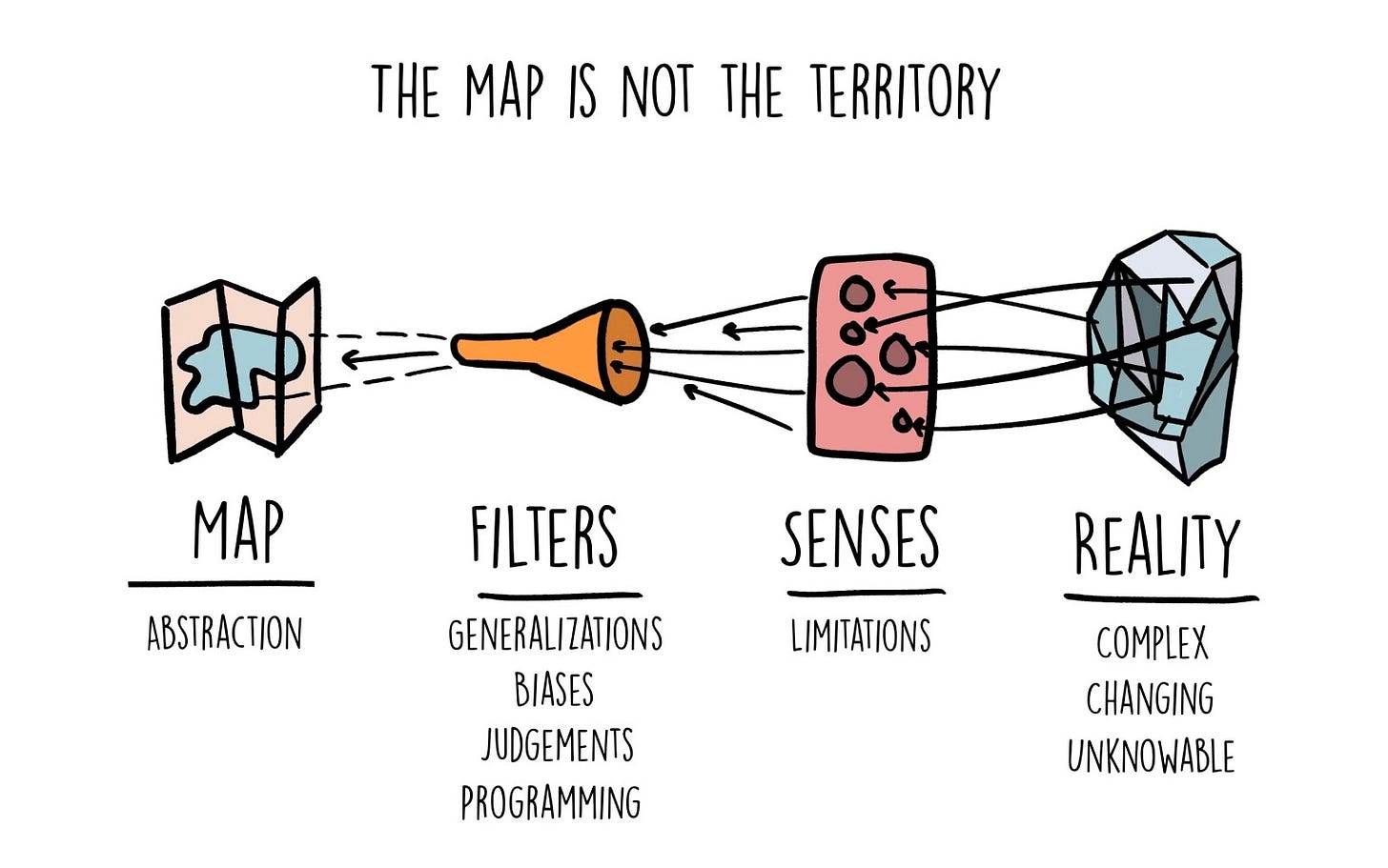

The Map vs Territory Fallacy

Simplified models (the map) hide the complexity of reality (the territory).

Case Study (a short story)

Amazon’s Customer-Service Metrics vs Reality

There is a famous story from Amazon’s early years where CEO Jeff Bezos encountered firsthand how map-vs-territory gap can blindside businesses

A weekly review consistently showed reported call-center wait times under 60 seconds, yet some customer complaints painted a different picture. Bezos told his team, “When the data and the anecdotes disagree, the anecdotes are usually right.” So, to test it, he picked up the phone and waited on hold himself, over ten minutes passed before he reached service. This uncomfortable experiment proved the metric was wrong: the “map” said customers waited a minute, but the territory that Bezos visited (an actual call) took far longer. By confronting the reality directly, he forced the team to fix both the customer service and the flawed data collection.

Framework to avoid the “Map Trap” : Paranoia, Skepticism, and First Principles

To avoid “the map trap”, leaders need a mindset of constant scrutiny. In a great post by “The Farnam Street,” a blog I personally recommend a post offers three principles to avoid the trap:

“Reality is the ultimate update,” models must be revised whenever new evidence appears.

“Consider the cartographer,” question the sources used and who built the metric, and why.

“Maps can influence territories,” consider that acting on flawed maps can alter reality itself. When data sources are biased or outdated, our actions based on those data can create self-fulfilling or destructive outcomes if unchecked.

When metrics conflict or look too neat, the smartest move is to step back and get qualitative feedback. Build minimal plans but be ready to rapidly pivot when reality calls. And here it is very important to apply first-principles thinking, which is to strip each assumption to its fundamentals and verify it with facts. If a report assumes 100% product quality, find a way to sample tests or customer returns to validate that assumption. The key is to treat a dashboard not like a conclusion of the experiment, but as hypotheses to test.

Questions to bridge the gap between the “map” and “the territory”

Strategy & Planning: Do we review our strategies and forecasts regularly against real-world insights? What assumptions would break under unexpected conditions? Why? What would the implications be?

Field Engagement: How often do our executives visit customers, front-line staff, or service centers to see the territory firsthand? Do the on-site observations match our metrics?

Report Integrity: Have we audited our data pipelines? Could collection methods or definitions be skewing our numbers? Are we confident in what we collect and how we collect it?

Management Interaction: Are managers routinely encouraging people to question the numbers? Or do we reward only “good” news on the dashboard? What disconfirming evidence do we have for the results in the reports?

Pressure-Testing Assumptions: What formal processes do we use to challenge our own data, i.e. scenario planning, pre-mortems, or first-principles workshops? Are different viewpoints (analytic and human) combined before decisions?

Metric Focus: Are we watching for correlated signals? Could we be fixated on one KPI while ignoring others? Do we know which indicators are leading vs. lagging? Do we leave in a lagging, leading or predictive work by the sum of metrics we collect and evaluate?

It is very dangerous to mistake the map for the territory, by the time you discover a false metric the hard way, it may be too late. The terrain you operate in, the business landscape, is always shifting, thus your models must shift accordingly or you’ll be lost. Only by fusing data with direct observation and first-principles reasoning can you be positioned to help navigate uncharted realities without being blindsided.

We use maps to simplify complexity, but never confuse the simplification of reality with reality itself.

“Only the paranoid survive.” Andy Grove

P.S. Before I go, here you have “The Treat,” where I share some of the music that kept me company while writing … Enjoy as you bid farewell to this post

“Lead yourself, Learn to live. Lead others, Learn to Build.”

If you enjoyed reading this post consider subscribing to the newsletter for free, joining the community and sharing your thoughts.